Extreme Climate Survey

Scientific news is collecting questions from readers about how to navigate our planet’s changing climate.

What do you want to know about extreme heat and how it can lead to extreme weather events?

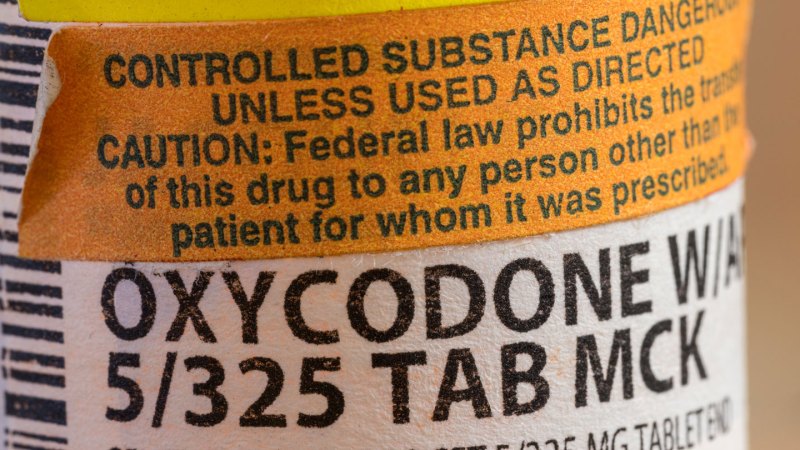

More than 80,000 people in the United States died from opioid overdoses in 2023, so a new prevention strategy could save lives. But Xu is careful to point out that the study doesn’t prove the drug curbs opioid overdoses. “We can only say that semaglutide is associated with reduced risk,” she says.

The findings set the stage for clinical trials directly testing the effects of semaglutide, Xu adds.

The new work is the first to suggest that this type of drug can have such a protective effect in humans, says behavioral neuroscientist Patricia “Sue” Grigson of Penn State College of Medicine in Hershey. “And that’s a pretty remarkable discovery.”

Semaglutide belongs to a family of drugs that mimic the gut hormone GLP-1 (SN: 29.8.23). Originally approved for diabetes, semaglutide and its relatives have gained notoriety—and notoriety—in recent years as weight-loss medications.SN: 12/13/23). But evidence is mounting that the drugs can do more than help people with diabetes and obesity — they appear to be a kind of medical Swiss army knife.

Studies in rats and mice have suggested that semaglutide may inhibit addictive behaviors (SN: 8/30/23). Early results from Grigson’s team suggest that a related drug, liraglutide, reduces opioid cravings in people with opioid use disorder (SN: 17.2.24). And a handful of studies from Xu’s team this year suggest that semaglutide may offer some benefits to people addicted to alcohol, tobacco and cannabis.

For the latest study, Xu’s team analyzed the electronic health records of more than 33,000 people who had been prescribed semaglutide or a handful of other diabetes medications and counted opioid overdoses over the next year. Although the overall number was low, people prescribed semaglutide were less likely to overdose than people prescribed other medications. Researchers recorded 35 overdoses in 2,605 people on semaglutide, for example, compared with 76 of 2,605 people taking metformin.

Scientists do not know why semaglutide may have this protective effect. It’s possible that people on medication crave opioids less and simply don’t use as much of the drug. That would make them less likely to overdose, Grigson says.

In November, Grigson’s team will begin enrolling people with opioid use disorder in a new clinical trial. Participants will receive semaglutide along with one of two standard treatments for the disorder, and researchers will track how the drug combinations affect their ability to abstain from opioids.

And Xu’s team has now set its sights on stimulants: Perhaps semaglutide could help people who use methamphetamines and cocaine. She thinks the drug may interfere with some of the biological mechanisms that drive drug cravings in general.

Pharmacoepidemiologist Serena Jingchuan Guo wonders if the drug could be used the day before addiction sets in, for example as part of a pain management plan for patients prescribed opioids for post-surgery pain relief. Perhaps taking semaglutide at the same time could prevent people from becoming addicted to opioids in the first place, suggests Guo, of the University of Florida. in Gainesville.

But she cautions that many questions about semaglutide and its relatives remain, such as the molecular buttons the drugs are pushing in the body to trigger their various effects. People think of it as a “miracle drug,” she says, but “there are so many unknowns.”

#Semaglutide #reduce #opioid #overdoses #study #suggests

Image Source : www.sciencenews.org